Hi Res Audio hear what you've been missing

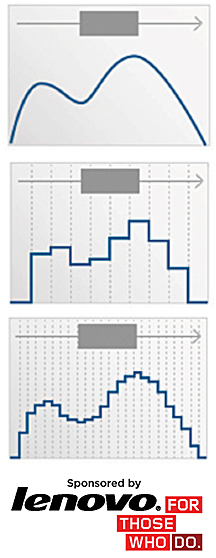

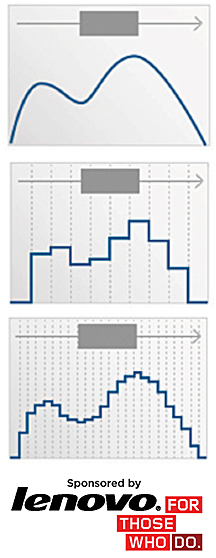

Original Analog recording (top) MP3 recording – 16bit /44.1kHz (center) Hi Res audio recording – 24bit/192kHz (bottom) Chart courtesy of Sony Corp.

By Gary M. Kaye

Chief content officer,

www.intheboombox.tv

When I got my first job out of college I invested in a good audio system. Back then it was a Harman Kardon Citation amplifier and pre-amp, a Bang & Olufsen straight-arm turntable, a Kenwood tuner, and a set of Bose 901 speakers.

For decades those remained the center of my home entertainment system. As I got older, and had kids, music evolved, and not always for the better, though certainly for the more convenient. The television became the center of home entertainment, no longer the stereo. Portable music went from cassette players, to CD players, to MP3 players, and while the convenience increased, the quality of the music decreased.

Generations of us accepted the trade off. Still, there were those amongst us who held on to the old ways. They kept their vinyl records; they upgraded their systems, often putting anywhere from $25,000 to $250,000 and more into high-end audiophile systems.

At the recent Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, where monstrous UHD Televisions with 108-inch curved screens were grabbing the attention, about a mile and a half away from the main action, in a back room of the Venetian Hotel, there was a relatively small exhibit room devoted to what may just be the next big wave in music: Hi Res audio, also known as HD (for High Definition) Audio. This niche market is now experiencing a concerted industry effort to bring top-end audio back at an affordable (though not cheap) price.

Hi Res audio means digitized audio tracks that are significantly better quality than what you'll find on most download services. It's not as if these all just sprang up this week. For several years, Hi Res audio has been a thriving, though boutique industry. Now, with a big push from Sony and some other players, Hi Res audio promises to push out of the back rooms onto the main stage of the digital music business.

Just how good is it?

It's always difficult to describe something better than what you're used it. Only in this case, it's a little like back to the future. Remember those vinyl albums from your youth or young adulthood? It's like that, only without the dust and scratches. With a good "live" recording you felt like you were sitting in front of the stage. You could hear the artist's fingers sliding along the guitar strings, the vibrations of the violin strings, and the thump of the timpani. They're all back with Hi Res audio.

When I first listened to a demo of some Sony gear a couple of months ago, it almost took my breath away. There were sounds I had never heard on an MP3 recording. Here's the reason before the advent of the digital world, all recording was analog, and reproduced sounds as we heard them. Then, when digital came along, our music started coming on CDs good quality, but big files. In order to squeeze those files so they'd take up less room on our devices, the engineers came up with MP3, which was only an approximation of that original recording.

Now, Hi Res audio files take a step towards recreating that original analog experience with a much higher sampling rate, often better than CD quality. The graph shown above illustrates the comparison of analog, MP3, and Hi-Res.

You don't have to bust open your piggy bank to get started with Hi Res audio. A couple of hundred dollars will do. Of course, you can also invest tens of thousands in a system. But even at the entry level, you're going to notice, and presumably appreciate the differences.

The least expensive way to get started is by attaching a Digital Audio Converter (DAC) to your computer. The Dragonfly DAC from AudioQuest costs about $150 and will allow you to take Hi Res tracks that you've downloaded onto your computer and play them into either headphones or speakers. You'll need some specialized software to do that, such as the audio player from JRiver for about $50. Cambridge Audio makes a DAC for just under $200.

While your Hi Res tracks will sound better than MP3s on any good headphones, they'll sound great on headphones optimized for Hi Res. Most of us have heard of Sennheiser, which makes top end phones ranging from about $130 to $1,500. A company you may not have heard of is Grado Labs. We tried a set of their RS2i phones ($495) and were blown away at the accuracy of the sound reproduction without coloration. Grado's line of audiophile phones and earbuds ranges from just about $100 all the way up $1,695 for their top of the line professional model.

To move up to the next level, you'll want a Hi Res digital audio player that has internal storage, and a variety of inputs and outputs. There are a number of brands. Sony makes several Hi Res players ranging in price from about $800 to $2,000. We tried their HAP-S1/B player with 500 gigabytes (GB) of internal storage. Sony also makes a free app that runs on both iOS and Android that makes it pretty easy to wirelessly load music and control playback functions. Sony also makes two sets of Hi Res speakers, the SS-HA3/B ($350) and the SS-HA1/B ($800). Of course, you can go up, way up. Induction Dynamic ID1 tower speakers cost $13,000, each. Antelope Audio makes a range of digital audio gear that starts at just under $1,900 and ranges to more than $7,000.

There are also portable players that will fit in your pocket. At the lower end is the FiiO X3 at about $200, while Astell&Kern makes a range of devices from about $700 to $3,200.

Feuding formats

One of the things holding the industry back has been a confusing number of formats. Hi Res does not have a single standard. There are a variety of formats called FLAC, ALAC, AIFF, DDE and others. The audiophiles will keep on arguing over these audio files. But now Sony and others give you the ability to play back all or most of the formats, so you don't have to make a choice. The differences among them focus on sampling rates and compression. But no matter which way you hear them; they are all significantly better than the MP3s that most of us have gotten used to.

All about content

Another issue with Hi Res audio has been content. So far, this is still very much a boutique business. The largest player, HDTracks, has a substantial catalog that's still only a fraction of a percentage point of what's available in MP3 format. The download music stores that are out there such as iTrax, Blue Coast Records, and others often specialize in releases from one or two labels, or just a handful of artists.

If you're a dedicated fan of a particular artist, you may be able to find Hi Res tracks. But finding out which download store has which artists can be a time-consuming and often frustrating effort.

Cost is another factor. Hi Res albums often cost between $17 and $25. That's a lot more than your iTunes store albums, and in many cases you cannot download individual tracks, only the full album. The costs are not prohibitive, but do reflect the realities of the business. It costs money to get the rights to the original master tapes and then recompile them digitally and re-release them. And, since this is still a relatively small-scale business, the sellers so far really can't enjoy economies of scale.

The Hi Res audio business is clearly picking up steam. Each week there are new Hi-Res versions of old albums coming to market and new artist recordings as well. The range of gear is growing, some of it with entry level prices. I expect that at next year's Consumer Electronics Show, Hi Res audio will be making a much bigger noise.

You can find another good comprehensive article that's a primer on Hi Res Audio online at:

www.whathifi.com/news/high-resolution-audio-everything-you-need-to-know.

Gary Kaye is the creator of In The Boombox ( www.intheboombox.tv), the first website to cover technology from the Baby Boomer perspective. Kaye has been covering high tech for more than 30 years with outlets including NBC, ABC, CNN and Fox Business. He is a regular contributor to AARP and other websites on issues regarding the nexus of technology, seniors and baby boomers.